Welcome to Game Development with Python!¶

The goal of this site is to open new worlds and possibilities to you in the area of computer programming. In this week we’ll motivate learning to program by exploring gaming. Today’s video games are complex masterpieces and are programmed by teams of programmers, artists, and writers. Yet, video game programming remains a very elite area with a huge amount of competition. So, my goal is not to teach you to be a video game programmer, but to teach you to be a programmer by learning about video games and how they are constructed. More importantly, the skills and knowledge you learn by studying Computer Science will open the door to a profession full of creativity, opportunities for life-long learning, and the skills needed to help many people.

There are a few basic things you need to learn to become a computer programmer. In the early lessons this week we’ll study the Python programming language and learn some of the basics. Just as importantly there are also skills we need to learn to find problems in our code. We almost never write code correctly the first time. We have to debug our programs until they are correct. Don’t worry if your program doesn’t run the first time you run it. It probably won’t. Programs working the first time they are run is the exception, not the rule. Try the code you have written. When it doesn’t work, try to figure out why. If you have spent a few minutes with the code and you are not sure of the problem, then ask for help. There is no problem in asking questions.

In Computer Science, we never write anything ourselves from scratch. Instead, we build on the shoulders of the giants that have come before us. Writing programs is a creative process and the design and coding of new creations (our programs) can be very rewarding, both emotionally and monetarily. But we all must acknowledge as programmers we don’t write things from scratch. Instead, we build new things by using code that others have written before in new and creative ways. Much of what we do as programmers relies on libraries of code that others have already written to make our job easier. So, an important part of computer programming is reading, trying out libraries of code, and figuring out how to use it in building something new.

As programmers we use our creativity and ingenuity to take code from libraries and combine these libraries along with code we write, to solve problems that impact the lives of those around us in some manner, hopefully for the good of humanity. We’re very excited to have you begin this journey, so let’s get started!

Getting Started¶

We are going to learn to program using a very popular programming language called Python. The language is named Python after Monty Python. It was first created by Guido Van Rossum, a programmer who worked for Google for a while and now works for Dropbox. Python is a language that is used by many websites to access data on web servers. It is also a language that will let you quickly learn to program. You can write a one line program in Python.

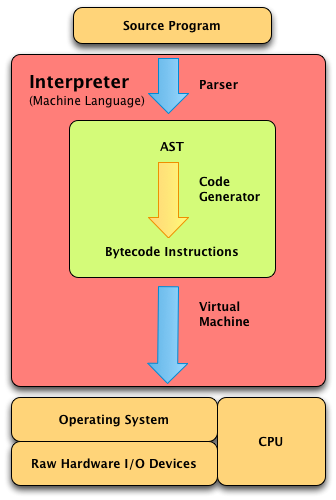

Python is a high-level language, meaning that we can do a lot with very few statements and instructions to the computer. For instance, we can build a list of values from a file with one line of code. But, to accomplish these high-level tasks, we need a program to help us. Python is an interpreted language and that means that a special program, called the Python interpreter, translates the high-level statements that we write into the low-level commands understood by a computer.

The figure below has the interpreter represented in Pink/Red. The internals of the interpreter (i.e. the stuff inside the Pink box) is not important to us. What is important is the source program which is interpreted by the Python interpreter, which is a program that understands how to run your source program using the operating system and the computer hardware. So, to run a Python program we must run it with a Python interpreter.

Configuring Python¶

To run Python programs you must have a Python interpreter installed. There are two versions of Python, version 2 and version 3. We’ll be using Python version 3 for our programming.

We’ll download a version of Python that has lots of modules which provide code for us to use. Anaconda is a large distribution of Python with lots of great modules available to use. We first bring up a web browser and go to http://anaconda.com. Then download version 3 of the anaconda distribution. Install the anaconda distribution on the computer. Usually it is just installed in your home directory. Then we can add the anaconda bin directory to your path. How to do this depends on your operating system. If you are using Windows, you edit the PATH environment variable using the Windows method of modifying the path. If you are using Mac OS X then you must edit the PATH environment variable by editing the .bashrc file in your home directory.

After installing anaconda, several other packages must be installed. First install keras. To do this you execute this command from a command prompt on the system.

conda install keras==2.1.2

Then pydot and graphviz must be installed. For our purposes later it is probably best to have pydot version 1.2.4 installed and graphviz version 2.40.1. Both pydot and graphviz are available as add-ons to the anaconda distribution of Python.

conda install pydot

conda install graphviz

Finally, we need to install the pygame module so we can use it while building some games. Pygame is not available as an add-on to the anaconda distribution but is available as part of Python so we use the pip command instead which is the Python install program (i.e. pip).

pip install pygame

This concludes installing all the Python software we’ll need for working through the problems on this site. Next we’ll configure a tool for writing software to play games.

Configuring the IDE¶

To write our Python programs we’ll use an Integrated Development Environment, or IDE, that runs the interpreter by providing it with your source program. Wing IDE 101 is our development environment.

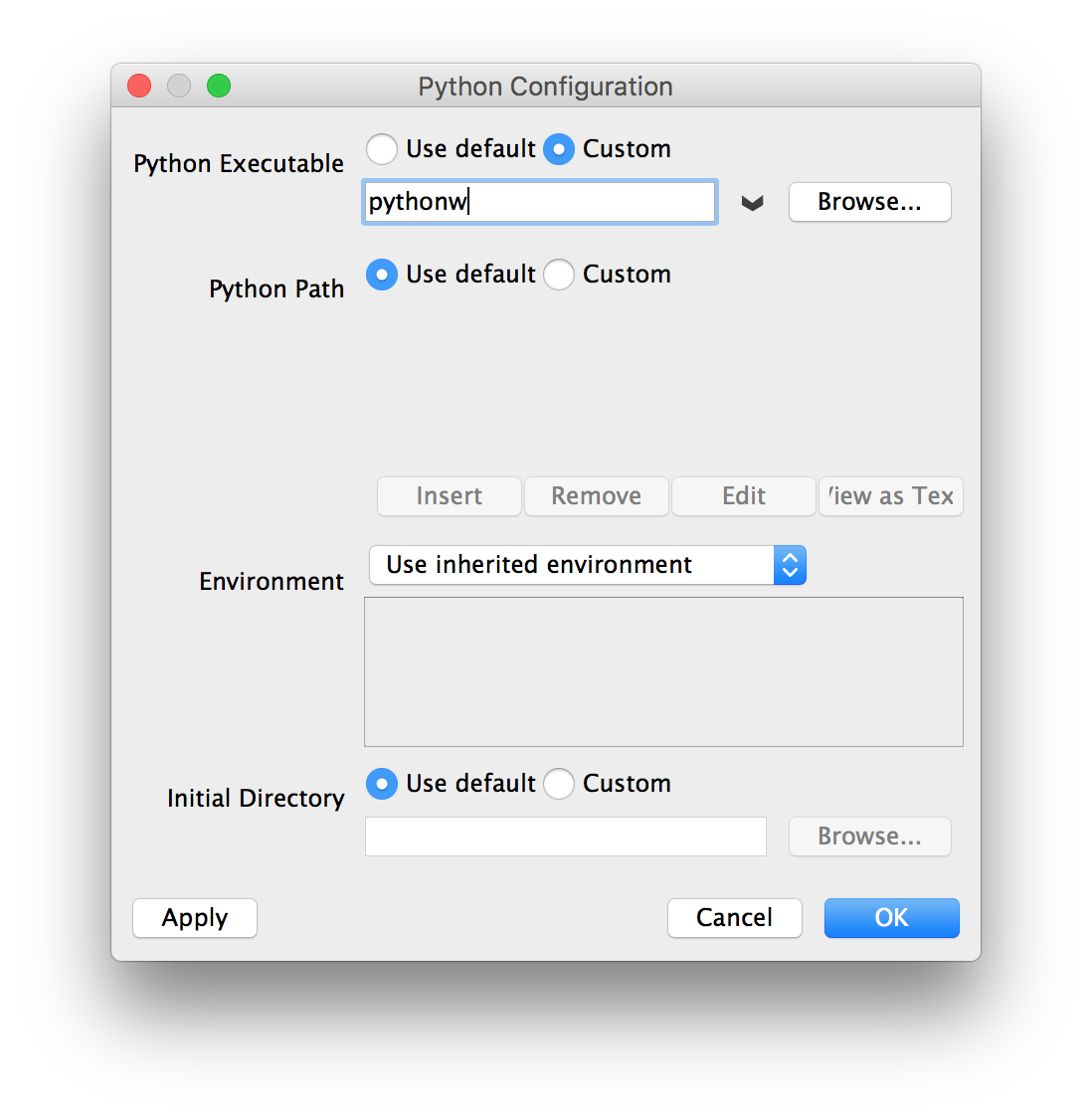

Start up the Wing IDE 101 program. The first time you run it you must accept the license (it is free to use) and then configure it to run our distribution of Python. To configure Wing IDE 101 choose Edit -> Configure Python… and then pick the right Python interpreter. In our case we’ll choose pythonw because this Python 3 interpreter will capture the keystrokes on the keyboard correctly to interact with games developed with pygame.

Press OK to accept pythonw as the interpreter. Wing 101 will ask if you want to restart the shell which is just another name for the Python interpreter. You can respond by clicking the restart shell button.

This is a one-time only configuration. Now, let’s write our first program.

Lesson 1¶

From this lesson we learn how to create a program in Wing IDE 101, save it, run it, and interact with it.

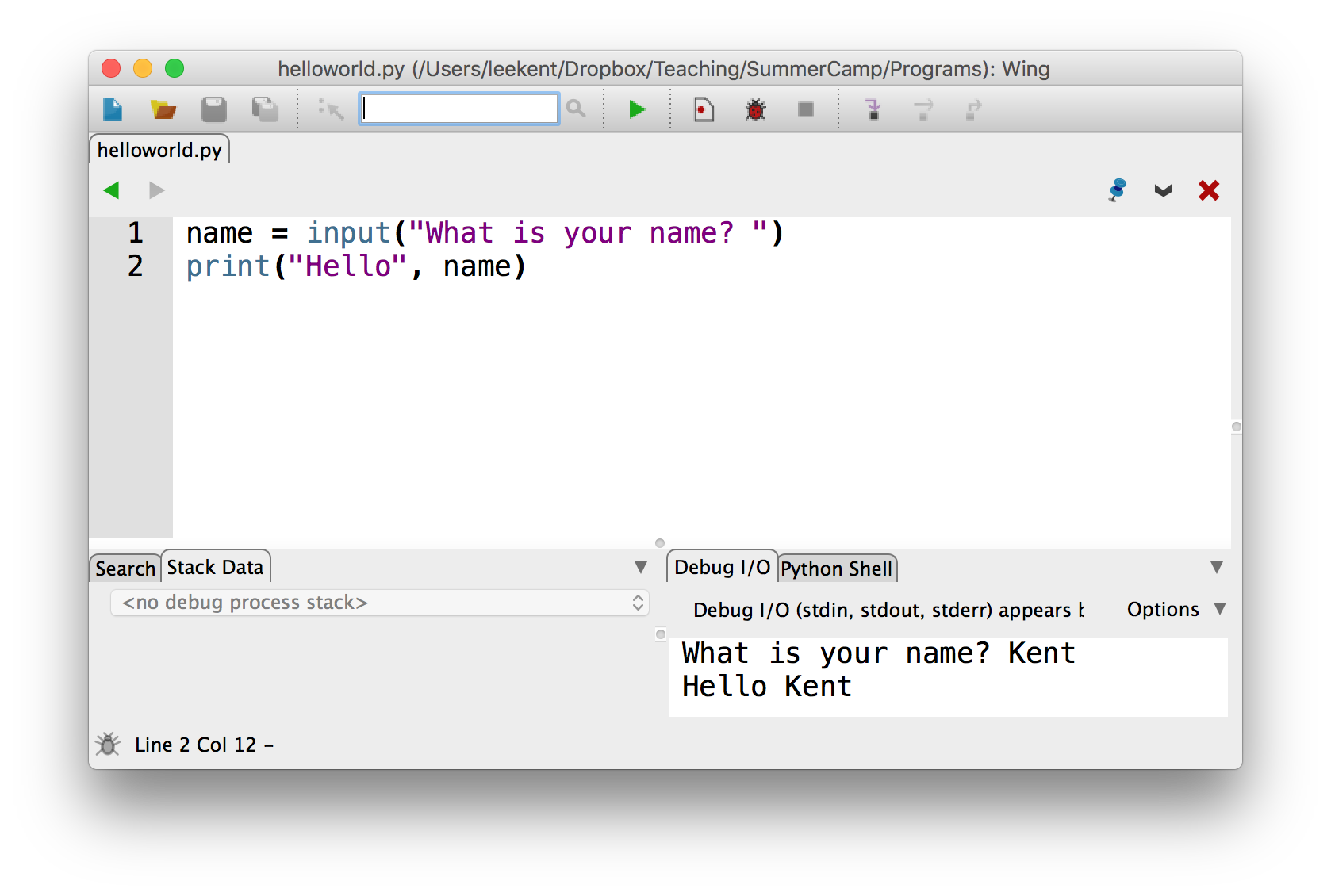

The first program is almost always a hello world application. We’ll start that way to keep things very simple, but with just a little extra. First start Wing IDE 101 and click the new program button. Then type the code from the figure below into the “untitled” pane. Once you are done typing it you can run it by clicking the bug icon. This icon is used to run and debug your program.

When you first run it you will be asked to save it. Save it to your Desktop folder and call it helloworld.py with no spaces and no capital letters.

The program will wait for input from you. You have to type your name in the Debug I/O pane. Then it will finish printing its output.

Next, let’s run it by stepping into it. Click the step into arrow on the right side. Then click the step over button to watch the Python interpreter execute each of the two statements.

By clicking in the gray strip just to the right of the line numbers you can also set breakpoints. A breakpoint looks like a stop light. When a breakpoint is encountered during execution of the program the program stops just before the statement is executed.

Try using step into, step over, and setting a breakpoint to make sure you know how they work.

Introduction to Types and Calling Functions¶

Python supports doing math involving two different types. There are integers and floats in Python. We’re familiar with integers. Floats are floating point numbers which are the computer’s version of Real numbers.

We can assign a variable a value. So for instance,

x = 6

This assigns the variable x the value 6. The 6 has a type which is an integer, or int in the Python language. The x is a variable which is a reference to the value. A reference is a pointer to a value. A value is also known as an object. So 6 is an integer object.

There are other types of values in Python. For instance, writing

y = 6.0

creates a variable reference y that points to a float object. Writing a decimal point in a number makes it a float instead of an int.

There are other types of values as well in Python. Strings are another example. In the first program above we have a string literal value show up when we wrote “Hello”. Strings are called the str type in Python. String literal values are written inside either double or single quotes.

The first program we wrote above calls two functions, the input function and the print function. A function is given a value or values and returns a value. The values given to the function are written inside the parens. If there is more than one, they are separated by commas. You call a function by writing its name. When a function is called you go to that function’s code (which you might not see) and execute its code. When the function is done executing it returns. A function always returns a value. Sometimes we care about the value the function returns. Other times we might not.

The input function gets input from the user and returns a str of that input. The input function is passed a prompt string to print when it is executed. The prompt is printed to the screen and then the program stops and waits for enter to be pressed. Any input typed before enter is pressed is returned from the input function as the value of the input. In the program above the input function is given the string literal value “What is your name? ” and it returns the input entered by the user.

The print function is given the two strings to print. The first string is the string literal “Hello”, the second string to print is the value entered by the user. The print function prints the values passed to it to the screen separated by spaces. Notice that more than one value can be passed to some functions, like print. When more than one value is passed to a function, we separate the values by commas. The print function returns a special value called None which we don’t care about so we don’t bother writing

val = print("Hello",name)

because val would just refer to the value None anyway and we don’t need that value in our program.

Converting Between Types¶

We can convert from one type to another by writing the name of the type like a function in Python and passing in the value we want to convert to a new type of value. For instance, consider getting the age of a person from the user.

name = input("What is your name? ")

myAgeStr = input("What is your age? ")

myAgeInt = int(myAgeStr)

print(name, "next year you will be ", myAgeInt+1)

Examine the code above closely. The myAgeStr is a string because that’s what input returns. The myAgeInt is an integer because we call the int type conversion function on the string.

Normally we might simplify the code above to look something like this.

name = input("What is your name? ")

myAge = int(input("What is your age? "))

nextYearsAge = myAge+1

print(name, "next year you will be ", nextYearsAge)

The code above has an assignment statement that assigns the value computed from myAge+1 to the variable nextYearsAge. Alternatively, you can increment the age. So you could write the code like this as well.

name = input("What is your name? ")

age = int(input("What is your age? "))

age = age+1

print(name, "next year you will be ", age)

This code demonstrates that you can re-use the same variable and increment it in the program. Re-using the same variable works well when you want to keep track of some accumulating value.

Arithmetic Operations¶

Notice that we added 1 to an integer in the code in the previous section. Integers and floats support all the common arithmetic operations include +, -, *, and /. Integers support // which represents integer division. So 6//4 would be 1. Integers also support the modulo (i.e. remainder) operator so 6%4 is 2. This is division like you learned in grade school. When you divide 6 by 4 you get 1 with a remainder of 2.

Strings support a few arithmetic operators as well like +, which is used for string concatenation. The * operator can be used with an integer to get string repetition. Here are some sample operations with strings.

Kent's Mac> python3

Python 3.6.5 |Anaconda, Inc.| (default, Apr 26 2018, 08:42:37)

[GCC 4.2.1 Compatible Clang 4.0.1 (tags/RELEASE_401/final)] on darwin

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> 6 + 5

11

>>> "hi"*6

'hihihihihihi'

>>> "hi " + "there"

'hi there'

>>>

In the code example above I wanted to try out something in Python. You can do this in two ways. You can open a terminal window and try it there. To do this go to the search icon at the top of the window, and type terminal. Then you can type python3 to start the interpreter. Once you have tried out what you see here you can type ctl-d to get out of the interpreter or just close the window.

The other way to try something out quickly is in Wing IDE 101. Click on the Python Shell pane and then you can try it right in that pane. You DON’T need to type ctl-d inside Wing IDE 101 to get out when you are done using the Python Shell in Wing.

You can get more help with arithmetic operators in Python by going to this page.

Lesson 2¶

Write a program that calculates the number of years since the Declaration of Independence was signed in 1776. Interacting with the program should look exactly like this.

What year is it? 2021

It has been 245 years since the Declaration of Independence was signed.

Once you have completed your solution, you can check it here.

String Operations¶

Strings are another built-in type in Python. String objects have a number of functions that we can call on them. When a function is associated with an object the function is called a method. To call the method we write the reference to the object first, followed by a dot, followed by the method name. For instance, there is a method called lower that returns a new string with all the characters of the object lower cased.

So if we execute this code…

s = "Hello WORLD!"

t = s.lower()

print(t)

it prints the string “hello world!” to the screen. There are many other methods that work on strings as well. They are listed in the String documentation.

Lesson 3¶

Write a program that asks the user to type a sentence and then prints all the lower case characters as upper case and all the upper case characters as lower case. So interacting with it should look like this…

Please type a sentence: Hello WORLD!

Here is the new sentence: hELLO world!

Once you have completed your solution, you can check it here.

If Statements¶

There is another type in Python for true or false. Boolean values, called the bool type in Python, are True and False. Using Python we can compare two values and get a boolean value as a result. Then we can execute one block of code or another based on that result. The then part is executed if the boolean value is True in an if statement, and the else part is executed if the value is False in an if statement.

For instance, consider this code.

dogName = input("What is your dog's name? ")

if dogName == "Fido":

print("That's not very original.")

else:

print(dogName, "is a cool name!")

We can also compare values for less than or greater than, less than or equal and greater than or equal.

age = int(input("Please enter your age: "))

if age < 1:

print("No your not!")

else:

print(age,"is a good age!")

if age < 1:

print("Younger than the first year, really?")

elif age < 13:

print("Those are great years!")

elif age <= 19:

print("You are a teenager! Oh boy!")

elif age < 26:

print("Your brain is still growing until you are 26. Did you know that?")

else:

print("Congratulations!")

if age >= 8:

print("You are ready to start learning to program!")

Lesson 4¶

Write a game that asks the user to think of a number between 1 and 100 (inclusive). Then check to see if the number is 50 or not and if it is, print that it guessed right. So running the program would look like this if the user thought of 50.

Pick a number between 1 and 100.

Is your number 50? Yes

I guessed correctly!

And, if the number was not 50 then it should run like this.

Pick a number between 1 and 100.

Is your number 50? No

I guessed incorrectly!

This seems like a silly exercise. But it will get you writing some code with an if statement. You can compare strings with == and != for equals and not equals. However, strings are either lower case or upper case. If you have a string named s and you want to lower case it you can write s.lower() to lowercase the string.

Once you have completed your solution, you can check it here.

Introduction to While Loops¶

We can make the guessing game in the last lesson more interesting if we allow the program to repeatedly guess numbers to find the correct answer. A while loop is just the trick. A while loop has a loop body which is a sequence of statements that will be executed as long as the condition of the while loop evaluates to True. Here is an example of a while loop.

count = 0

while count < 10:

print(count)

count = count + 1 # you can abbreviate this as count += 1

Run this code to see that it repeats the print and the assignment statement 10 times, printing 0 through 9 to the screen.

Lesson 5¶

We can improve the guessing game by keeping track of two values a low and a high integer. Then each time through the loop we’ll guess the integer average of the low and high value. If we are wrong we should ask if the number is lower or higher. If it is lower then we can adjust the high value. If it is higher than the average, then we can adjust the low value. In this way we keep repeating the body of the loop until the value is found.

We can start the program by setting up the loop as follows.

...

found = False

while not found:

# This is the body of the loop where we guess and then adjust low and high as

# appropriate.

You fill in the blanks in this code so interacting with the program works like this.

Pick a number between 1 and 100

Is your number 50? no

Is it higher or lower? higher

Is your number 75? no

Is it higher or lower? lower

Is your number 62? yes

I guessed correctly in 3 tries.

Once you have completed your solution, you can check it here.

Two Container Types¶

There are several types built into Python for containing other values. These types are called container types or container classes. Tuples, lists, sets, and dictionaries are four of the common container types available in Python.

We want to learn about these container types because we are going to write programs that often have more than one value that we must keep track of. When we do, we want to use one of these containers if possible. For each of the containers we need to know how to create a container object, how to put things in it, and how to get things back out of it. The things we put in containers are called elements because containers are written so that practically any kind of element may be added to a container.

Tuples¶

There are four different kinds of collections that are important for us as computer programmers. We will first look at tuples. A tuple is a sequence of values that cannot be changed once the tuple is created. For instance (4,3) is a tuple of two integers. Here is some code that works with tuples.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 | x = (4,3.0)

y = x[0]

z = x[1]

print("x =",x)

print("y =",y)

print("z =",z)

a,b = x

print("a =",a)

print("b =",b)

c = (a,b,x)

print("c =",c)

|

Running this code produces the following output.

x = (4, 3.0)

y = 4

z = 3.0

a = 4

b = 3.0

c = (4, 3.0, (4, 3.0))

The tuple (4,3) is assigned to x on the first line. The second line takes the zeroth element of the tuple and assigns it to y. Tuples are immutable sequences. Tuples being immutable means we can’t change the elements of the sequence once the tuple has been created. Elements of sequences, like tuples, are given index positions starting at 0. So x[0] is the first element of the tuple. Then x[1] is the second element of the tuple.

Using Python you can assign variables to each element of a tuple by separating by commas. Line 7 of the code above assigns a and b to the individual elements of x. Finally, line 10 shows that a tuple may contain other tuples.

You can read more about tuples by clicking here.

Lists¶

Lists are similar to tuples, except that we use a slightly different syntax for creating a list and lists are mutable while tuples are immutable. This means that lists can be modified once they are created. Consider this code.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 | lst = []

lst.append("hi")

lst.append("there")

print(lst)

y = lst[0]

x = lst[1]

print(x)

print(y)

lst[1] = "Bob"

print(lst)

s = "Hello World\tHow,\tare\nyou?"

print(s)

sList = s.split()

print(sList)

|

Line 1 of the code above creates an empty list. Lines 2 and 3 add to elements to the list, mutating it so it is no longer empty. Line 4 prints the list. Take a look at the first line of output below to see what a list looks like when printed. Like tuples you can access individual elements of a list as shown on lines 5 and 6. Take note of the fact that the indices into a list start at 0 and go to 1 less than the length of the list. Line 9 shows how an element of a list may be mutated to hold a new value.

Line 13 shows how a string can be split by calling the split method which returns a list of the white space separated values in the string. White space are any blanks, tabs, or newline characters found in the string. Take note of how the tab character (i.e. \t) and the newline character (i.e. \n) are encoded in the string and how they affect the output coming from the program.

['hi', 'there']

there

hi

['hi', 'Bob']

Hello World How, are

you?

['Hello', 'World', 'How,', 'are', 'you?']

More information on using lists can be found here.

Patterns of Computation¶

In the following sections we’ll learn about several patterns for computing things involving lists of elements. These patterns are used over and over again in writing code. Each section will introduce one of these patterns through an example. You should take a moment in each section to understand how these patterns can be applied to lots of different situations.

For Loops for Lists¶

Lists are collections of elements. We keep elements in a list when the elements are all alike in some way. We might have a list of integers, or a list of strings. We can even have lists of more complicated values like employees or students. For now, we’ll limit our discussion to lists of strings and integers.

When we have a list of elements we may want to do something with each element of the list. This is where a for loop comes in handy. A for loop iterates (i.e. repeats) once for each element of a list. Here is a loop that prints the elements of a list.

1 2 3 4 5 6 | s = "Hello World\tHow,\tare\nyou?"

print(s)

sList = s.split()

print(sList)

for element in sList:

print(element)

|

This for loop prints each of the elements of the list.

Each list, like tuples, has index values that can be used to get individual elements of the list. Consider this code.

1 2 3 4 5 | s = "Hello World\tHow,\tare\nyou?"

print(s)

sList = s.split()

print(sList[0])

print(sList[1])

|

So sList[0] is the first element of the list. There is a len function that can be used to get the length of a list. There is also a range function that will generate a list of integers, which can be used as the indices into a list. So this code will work to print the elements of a list as well.

1 2 3 4 5 6 | s = "Hello World\tHow,\tare\nyou?"

print(s)

sList = s.split()

print(sList)

for i in range(len(sList)):

print(sList[i])

|

The range function can be given three arguments. It can be called as range(start,stop,increment) and it generates a list of integers from start to stop-1 that goes up by increment each time. So range(0,10,2) would generate the list of integers [0,2,4,6,8] but not 10 because range only goes to stop-1 which would be 9 in this case.

We can also generate ranges that go backwards. So, range(9,-1,-1) would generate the list [9,8,7,6,5,4,3,2,1,0]. This can be used to build a more flexible for loop for going through elements of a list. For instance, if we want to use a for loop to go backwards through a list we can write the following.

1 2 3 4 5 6 | s = "Hello World\tHow,\tare\nyou?"

print(s)

sList = s.split()

print(sList)

for i in range(len(sList)-1,-1,-1):

print(sList[i])

|

The code above will print you? first and Hello last.

Importing Modules¶

A module is code that someone else wrote and that we can use. It is frequently useful to use code that others have already written so we don’t have to start from scratch for each program we write. We also know when we import a module that the module has been debugged and should work as described. We import a module by writing

import module_name

where module_name is the module to be imported. Many, many modules are already written for Python. Included among them is the random module.

If we import the random module we can use code in it to build a random permutation of a list of integers. Here is some code that can be used to build a random permutation of a list of integers.

1 2 3 | import random

rng = range(10)

print(random.sample(rng,len(rng)))

|

To call the sample function from the range module, we write random.sample(arguments) to call it. To know what is in the random module, you have to read the random module documentation. Go there now to read about the sample function and what it does.

The Accumulator Pattern¶

The accumulator pattern is a pattern of statements that is frequently used for accumulating a value calculated from the values in a list. The general format of the pattern looks like this.

1 2 3 4 5 6 | accumulator = identity_value

for element in list:

accumulator = accumulator op element

# use the accumulated value in the accumulator.

|

For instance, if we want to add all the values in a list together we might write something like this.

1 2 3 4 5 6 | total = 0

for x in lst:

total = total + x

print("The total of the values in the list is", total)

|

This gives us the total numeric value. But, the same pattern might apply to concatenating all the strings in a list by writing this.

1 2 3 4 5 6 | sentence = ""

for s in sList:

sentence = sentence + s + " "

print("The sentence is", sentence)

|

The blank is added to put spaces between the words that are concatenated to the string.

There are many uses of this pattern. It can be used to find the product of a bunch of numbers. Sums and concatenations are the example given here. We can also use it in computing averages where we need the sum of the items and the number of items being averaged.

Lesson 6¶

Let’s use what we have learned to create a jumble of a word. For instance, if we have a word like “truck” then a jumble of it is “curtk”. Write a program that asks the user to enter a word and then prints a jumble of that word. Your program interaction should look like this.

Please enter a word: truck

A jumble is curtk.

You should make sure that your output is identical to this, except that you might have a different jumble.

The solution to this involves using a for loop and the accumulator pattern so this exercise brings a lot of things together that you just learned. To begin, write a program that prints out the same word that you type in. Then start expanding on it. Write a little bit, try it, then write a little bit more. This is called incremental programming.

Once you have completed your solution, you can check it here.

The Guess and Check Pattern¶

There is another useful pattern that shows up in many computer programs. The guess and check pattern is often used when dealing with a list of elements. If you need to know if a certain condition holds for some element of a list, then you want to use the guess and check pattern. The general pattern look like this.

guess = False

for element in lst:

if p(element):

guess = True

# after the for loop we know of p(element) was true for some element of lst

There are many variations of this pattern. For instance, if we want to know if an even number appears in a list we might write something like this.

lst = [7,5,4,3,1]

evenNumberExists = False

for element in lst:

if element % 2 == 0:

evenNumberExists = True

if evenNumberExists:

print("There was an even number in the list.")

else:

print("There were no even numbers in the list.")

Again, there are many different versions of this guess and check pattern. For instance, if we want to find the maximum value of a list of values we might do it like this. Assume that we know that all values are non-negative in a list that we are given. Consider this code.

lst = [3,1,5,4,7] # This is some collection of values given to us.

# -1 works as an initial value because it is less than any maximum value.

maxVal = -1

for x in lst:

if x > maxVal:

maxVal = x

print("The maximum value is", maxVal)

Reading a File¶

It is sometimes useful to read from a file using Python. There are several ways to do this. Since a file consists of many lines of text, you can use a while loop to read from a file. You may also use a for loop to read from a file. Consider reading from a file like the wordsEn.txt file. You can save this file by right-clicking on it and selecting Save Link As…. Save it to a file called wordsEn.txt. Then you can read this file by writing this. The file and the program must be saved in the same directory for this code to work.

file = open("wordsEn.txt", "r")

words = []

for line in file:

words.append(line.strip())

The code above builds a list called words that contains all the words found in the file. The call to strip removes any white space appearing before or after the word. You can achieve the same result by using this alternative code.

file = open("wordsEn.txt","r")

words = [x.strip() for x in file.readlines()]

This code relies on what is called a list comprehension to loop over the lines in the file and strip each line. The file.readlines() reads all the lines of a file and places them into a list of strings. The x.strip() for x in file.readlines() takes each element of the list and strips the whitespace which includes a newline character for each line of the file before it is stripped and removes those newlines. We end up with just a list of all the words in the file.

Word Permutations¶

Jumbles are permutations of words. A permutation is simply a rearranging of the elements of a list. In the case of jumbles, it is a rearranging of the letters of the string. Permutations are something that can be useful and someone has written a module for doing this. The itertools module helps in building permutations. For instance, to get all the permutations of the string “hello” we can use the following code.

import itertools

s = "hello"

lst = ["".join(x) for x in itertools.permutations(s)]

print(lst)

This code uses the itertools permutations function to get all the permutations of a string. However, calling the permutations function returns an object that when iterated over returns the permutations as tuples of characters like (‘h’,’e’,’l’,’l’,’o’) instead of as strings. So, the expression “”.join(x) takes a tuple of characters and joins them all together into a string. So, the list comprehension above returns the following list of values, which is the output from this code.

['hello', 'helol', 'hello', 'helol', 'heoll', ...]

Many of the permutations are omitted here since there are 5x4x3x2x1=120 permutations.

Lesson 7¶

Jumbles often appear in newspapers and on websites. In this lesson you’ll write a program that helps you solve jumbles. Ask the user to enter a jumbled word. Then print possible solutions to each jumbled word that is entered. For instance, interacting with the program should work like this.

What is the jumbled word? ipnut

Possible solutions are:

input

You can write this code by using the wordsEn.txt file, reading it into a list, and then checking each of the permutations of the jumbled word to see if they are in the list.

You can try these jumbles as well with your program: yamof, warely, and deonlo. One of them doesn’t behave quite right. Why is that? Form a theory and then check it out to see if you were right.

Once you have completed your solution, you can check it here.

Two More Container Types¶

Because of their importance to efficiency there are two more built-in types that we’ll cover, sets and dictionaries. These two collections are important because membership within them can be determined in constant time. That means that no matter how big the set or dictionary is, the amount of time needed to determine if an element is in a set or dictionary does not increase. You may have noticed in lesson seven that it took a considerable amount of time to determine what the jumbled word should be in some cases. This is because of the number of words in wordsEn.txt. As the size of the list of words grows, so does the time it takes to look up a word. One solution to this is to use a set.

Sets¶

A set is a collection of elements where there are no duplicates and where there is no ordering of them. Sets are simply collections of unique elements. Python has two different set types. The frozenset type is a set that cannot be altered after it is created. A set is a mutable (i.e. alterable) set of elements. Documentation on how to use both types of sets can be found here.

If we wanted to build a frozenset of all the words in the wordsEn.txt file all we have to do is add a frozenset type conversion to our list comprehension that builds the list of words.

file = open("wordsEn.txt","r")

words = frozenset([x.strip() for x in file.readlines()])

This gives us a frozen set. If we replaced the frozenset with set then we would have a set type of value. The need for the distinction between sets and frozensets will be clearer after reading about dictionaries.

Both set types support set operations like intersection, and union, and difference. There are mutating methods for the set type that also support mutating set operations like intersection_update, update, and difference_update. To learn more about these operations you can read the set documentation.

You can test for set membership using the in operator. So, the following code can be executed for a set of integers.

mySet = frozenset(range(10))

x = 6

if x in mySet:

print("Yes")

else:

print("No")

This code will print Yes when executed. If x=10 it would print No. As an example of computing the intersection of two sets consider this code.

firstSet = frozenset(range(10))

secondSet = frozenset(range(5,20))

thirdSet = firstSet.intersection(secondSet)

print(thirdSet)

When executed, this code prints frozenset({5, 6, 7, 8, 9}) as the result.

Lesson 8¶

Redo the jumble code from lesson seven to use frozensets instead of lists whenever possible. Make sure you have the same output as before. You should notice a significant speed up in finding the correct answers. Again, you can try out ipnut, yamof, warely, and deonlo. The interaction with the program should look like this.

What is the jumbled word? ipnut

Possible solutions are:

input

Once you have completed your solution, you can check it here.

Dictionaries¶

A dictionary, sometimes called a map or a hashtable, is a mapping of keys to values. A set is like a dictionary with only the keys being in a set. The dictionary, or dict type in Python, is used to map a key to a value for some set of keys. Here is an example of creating and using a dictionary in Python.

stateCapitals = {}

stateCapitals["MN"] = "St. Paul"

stateCapitals["IA"] = "Des Moines"

stateCapitals["WI"] = "Madison"

for state in stateCapitals:

print(state,stateCapitals[state])

if "ND" in stateCapitals:

print(stateCapitals["ND"])

else:

print("ND is not in the stateCapitals map")

The code above shows us that we can iterate over the keys in the dictionary by using a for loop. We can also use the subscript operator to get the value that goes with the key by writing stateCapitals[state] where state is that key.

The cool thing about a dictionary is that the keys can be virtually any value that is not mutable and can be compared for equality. So the key can be a tuple, a string, a frozenset, or an integer, or other immutable values. A key to a dictionary cannot be a set, or a list, or another dictioinary because these are mutable values.

Lesson 9¶

Create a dictionary that maps tuples of (row,col) to values of “X” or “O”. Then write two nested for loops that print a tic tac toe board. You should get the contents of the board from the user. So, interacting with the program should look like this.

Please enter the first row of the board : X O X

Please enter the second row of the board: X _ X

Please enter the third row of the board : _ O _

The board is currently this:

| X | O | X |

-------------

| X | | X |

-------------

| | O | |

When printing, if you don’t want to print a newline character at the end of a print, you can call print like this:

print("Hello World", end="")

and it will not print a newline at the end. In addition, if you want to print a newline someplace other than the end of a print, you can include the newline in the string like this.

print("Hello\nWorld")

These two hints may help in solving this problem.

Make sure you use two nested for loops to print the board back out once you have created the board dictionary. It will be helpful if you treat the first row as row 0 and the first column as column 0 so that board[(0,0)] is the upper left corner of the tic tac toe board.

Once you have completed your solution, you can check it here.

Writing and Calling Functions¶

As our programs get bigger we want to organize them and one of the major organizational tools in Python is the ability to define functions. A function has a name and is given arguments. The function returns a value. We call a function, which is a sequence of statements that are executed using the arguments provided to it. When the sequence of statements finishes, we return to where we called the function. Consider this code.

# This is a predicate function that takes an integer as an argument and

# returns true if the integer is even and false otherwise.

def isEven(x):

if x % 2 == 0:

return True

return False

# This function takes a list of numbers and multiplies all of them together

# and returns the product of those numbers.

def product(lst):

product = 1

for x in lst:

product = product * x

return product

# This is the start of code that is not in either function. This is the module level code.

evens = []

for x in range(1, 100):

if isEven(x):

evens.append(x)

evensProduct = product(evens)

print("The product of the even numbers between 1 and 99 is", evensProduct)

This code above is used to find the product of all the even numbers between 1 and 99.

Typically Python programs have a main function that is defined. The main function is defined to contain the top-level code of our program. It typically is not very complicated. If it gets too complicated we will usually figure out how to organize the program better to keep the main function simpler. Here is the general format for writing a main function and calling it using the above example again.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 | # import any modules at the beginning

def isEven(anInt):

x = anInt % 2

if x == 0:

return True

return False

def product(lst):

product = 1

for x in lst:

product = product * x

return product

# Typically Python programs have a main function someplace which is where

# the program begins execution (because of the call to it shown below.)

def main():

# This is the code in the main function of this program.

evens = []

for x in range(1, 100):

if isEven(x):

evens.append(x)

evensProduct = product(evens)

print("The product of the even numbers between 1 and 99 is", evensProduct)

# This if statement is at the module level. It is the only

# code that is at the module level in this program.

# By writing this if statement, if the program is run

# by itself then main() is called to run the program.

# If this module were imported into another program

# the following condition would be false and so

# the main function defined above would not be called.

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

|

There is another important concept to understand in regard to functions. A variable defined inside a function is only available in that function and not outside it. So for instance, the variable x, defined on line 4 in the isEven function, is not available outside of that function. The variable x that appears on line 24 in the main function is a different x. So when isEven is called on line 24 and then assigns a value to x on line 4, this is a different x than is being assigned a value on line 24 in the program. In this way, we don’t have to worry about what the names of variables are outside the function that we are writing. We know that anything we define inside a function is only defined inside the function and not elsewhere.

Lesson 10¶

Let’s take the code from the last lesson and modify it so that X’s are represented with 1’s and O’s are represented with -1’s. Zero can represent a blank spot. So, we can write code at the module level to be used as constants in our code. Take a look at this code below.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 | X = 1

O = -1

tokenToChar = {}

tokenToChar[X] = "X"

tokenToChar[O] = "O"

tokenToChar[0] = " "

def printBoard(board):

for i in range(3):

print("|",end="")

for j in range(3):

print(tokenToChar[board[(i,j)]]+"|",end="")

print('\n-------')

def main():

row1 = "X _ O".split() #input("Please enter the first row of the board : ").split()

row2 = "X X O".split() #input("Please enter the second row of the board: ").split()

row3 = "O O X".split() #input("Please enter the third row of the board : ").split()

board = {}

for i in range(len(row1)):

if row1[i] == "X":

board[(0,i)] = X

elif row1[i] == "O":

board[(0,i)] = O

else:

board[(0,i)] = 0

for i in range(len(row2)):

if row2[i] == "X":

board[(1,i)] = X

elif row2[i] == "O":

board[(1,i)] = O

else:

board[(1,i)] = 0

for i in range(len(row3)):

if row3[i] == "X":

board[(2,i)] = X

elif row3[i] == "O":

board[(2,i)] = O

else:

board[(2,i)] = 0

printBoard(board)

#print(evalBoard(board))

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

|

Take a look at the printBoard code and see how it works. Now, define another function called evalBoard which when it is called will return 1 if X wins, -1 if Y wins, and 0 if nobody wins or if there is no winner yet. Be sure to call your evalBoard function to try it out.

Once you have completed your solution, you can check it here.

Writing Classes, Making Objects, Calling Methods¶

As programs get even bigger, there needs to be even more organization to them. For instance, in the previous lesson we have developed two functions that both operate on a Tic Tac Toe board. It would be nice to group these functions together by tying them to a class of data. Classes are the means a programmer can describe a new type to Python and the operations that are allowed on that new type. Consider this code.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 | # This is the name of the new type (i.e. class).

class Kitty:

# Inside the class is anything indented inside it. This class

# extends to the "def main" below.

# This method name is the one given to the constructor. It exists

# so objects can be created as shown on lines 31 and 48 below.

# The constructor stores values in the object which is referred to

# by self.

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

# This is a method that has a side-effect. It returns None.

def speak(self):

print(self.name,'says meow')

# This is an accessor method since it access the name

# field of the object referred to by self.

def getName(self):

return self.name

# This is a mutator method since it changes the name

# field of the object referred to by self.

def setName(self,newName):

self.name = newName

def main():

# Here we create an object by writing the type's class

# name in this expression.

helloKitty = Kitty("Tigger")

# Here is how a method is called. We write the

# object . method ( arguments )

# to call a method. In this case there are no

# arguments because self is supplied by writing

# helloKitty on the left side of the dot.

helloKitty.speak()

# Here is a call to an accessor method. Notice we

# write helloKitty.getName() to call getName on

# the helloKitty object.

catName = helloKitty.getName()

print(catName)

helloKitty.setName("Curious")

# This creates a second Kitty object.

secondKitty = Kitty("Mother")

# Notice the two calls to speak. One

# on helloKitty's object and one on

# secondKitty's object.

helloKitty.speak()

secondKitty.speak()

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

|

The comments in the code above are important to review here. Take the time to review each line to see what it does and to familiarize yourself with the syntax. Then use the debugger to step into and over the entire program to watch how it executes. Check out the Stack Data pane in Wing IDE 101 so you can watch the objects as they are created and manipulated.

Operator Overloading¶

Because of its importance to understanding how some code works in Python, we’ll briefly go over operator overloading. Python allows certain operators to be overloaded like +, -, *, /, //, %, in, and many other operators that are covered here.

These operators are actually implemented as methods with special names in Python. For instance the __setitem__ and __getitem__ methods can be implemented to allow the subscript operator to be used on an object.

x = [1,2,3]

# Here is an example of __setitem__ being called on a list.

x[0] = 4

# Here is an example of __getitem__ being called on a list.

print(x[2])

The overloaded method is called when the operator is used in an expression.

The Tic Tac Toe board dictionary that we used in previous code could be implemented by writing a new class called TicTacToeBoard. But, we might still want to be able to set and get items from the dictionary as we did in the past. To do this we could write code like this.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 | X = 1

O = -1

tokenToChar = {}

tokenToChar[X] = "X"

tokenToChar[O] = "O"

tokenToChar[0] = " "

class TicTacToeBoard:

# The TicTacToeBoard contains a dictionary which is called data. This encapsulates

# the board into the TicTacToeBoard object and hides the details from those using

# the object.

def __init__(self):

self.data = {}

# Here is the set item magic method for the set item operator

def __setitem__(self,key,val):

self.data[key] = val

# And here is the get item method.

def __getitem__(self,key):

return self.data[key]

def main():

row1 = "X _ O".split() #input("Please enter the first row of the board : ").split()

row2 = "X X O".split() #input("Please enter the second row of the board: ").split()

row3 = "O O X".split() #input("Please enter the third row of the board : ").split()

# Notice that the board is created differently now.

board = TicTacToeBoard()

# __setitem__ is used in the code below.

for i in range(len(row1)):

if row1[i] == "X":

board[(0,i)] = X

elif row1[i] == "O":

board[(0,i)] = O

else:

board[(0,i)] = 0

for i in range(len(row2)):

if row2[i] == "X":

board[(1,i)] = X

elif row2[i] == "O":

board[(1,i)] = O

else:

board[(1,i)] = 0

for i in range(len(row3)):

if row3[i] == "X":

board[(2,i)] = X

elif row3[i] == "O":

board[(2,i)] = O

else:

board[(2,i)] = 0

# check out how the two methods below are now called. They

# are no longer functions. They are methods which are a part

# of the TicTacToeBoard class.

board.print()

print(board.eval())

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

|

Lesson 11¶

The code above shows us how we might define and use a new TicTacToeBoard class. It won’t work as it stands. To get the code above to work you must write the print and the eval methods of the TicTacToeBoard class. Complete this lesson by implementing these methods.

Once you have completed your solution, you can check it here.

Code Re-use with Inheritance¶

Inheritance is something we can use when writing classes so that we can re-use code that was written before. In some languages inheritance plays another role as well, but with Python the only reason for inheritance is code reuse.

Using our previous exercise as an example, the code below now inherits from dict instead of encapsulating a dict called data as in the last example. So, TicTacToeBoard is a dictionary and therefore does not need to have __getitem__ and __setitem__ written for it. This is the code re-use in this case. We automatically get these two methods because we are using inheritance. But, we still have to write the print and eval methods.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 | X = 1

O = -1

tokenToChar = {}

tokenToChar[X] = "X"

tokenToChar[O] = "O"

tokenToChar[0] = " "

class TicTacToeBoard(dict):

# In this version, the TicTacToeBoard inherits from dict which means that

# TicTacToeBoard is a dictionary and does not need the __getitem__ and __setitem__

# methods because they are already defined. In addtion, the constructor below

# doesn't do anything except call the super constructor which should always be

# the first thing you do in an inherited constructor so you call the original

# super class constructor to do whatever it needs to do. Sometimes you might write

# additional code after the call to super().__init__()

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

def main():

row1 = "X _ O".split() #input("Please enter the first row of the board : ").split()

row2 = "X X O".split() #input("Please enter the second row of the board: ").split()

row3 = "O O X".split() #input("Please enter the third row of the board : ").split()

# Notice that the board is created differently now.

board = TicTacToeBoard()

# __setitem__ is used in the code below.

for i in range(len(row1)):

if row1[i] == "X":

board[(0,i)] = X

elif row1[i] == "O":

board[(0,i)] = O

else:

board[(0,i)] = 0

for i in range(len(row2)):

if row2[i] == "X":

board[(1,i)] = X

elif row2[i] == "O":

board[(1,i)] = O

else:

board[(1,i)] = 0

for i in range(len(row3)):

if row3[i] == "X":

board[(2,i)] = X

elif row3[i] == "O":

board[(2,i)] = O

else:

board[(2,i)] = 0

# check out how the two methods below are now called. They

# are no longer functions. They are methods which are a part

# of the TicTacToeBoard class.

board.print()

print(board.eval())

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

|

Lesson 12¶

The code above shows us how we might define and use a TicTacToeBoard class that inherits from dict. It won’t work as it stands. To get the code above to work you must write the print and the eval methods of the TicTacToeBoard class. Complete this lesson by implementing these methods.

Once you have completed your solution, you can check it here.

Turtle Graphics¶

We are going to write a minesweeper event-driven application. To write the minesweeper application you’ll need to learn some things about Turtle Graphics. To use turtle graphics we create a turtle. The idea is a turtle runs around on the sand leaving a trail with its tail. In reality, sea turtles leave two tracks in the sand from their flippers. In the turtle graphics world the single trail can paint a picture. Actually, a turtle can do a lot more than leave a trail.

To create a turtle you start a new Python program and then write the following.

import turtle

myTurtle = turtle.Turtle()

Then, the identifier myTurtle represents or refers to a turtle. As we learned when calling methods, you can send commands to this turtle by writing the name of it followed by a dot (i.e. a period) followed by the command. For instance, to tell the turtle to go forward 50 steps you would write:

myTurtle.forward(50)

There are other commands that you might want to send to a turtle. Try these commands out to see what they do.

myTurtle.left(90)

myTurtle.right(45)

myTurtle.goto(100,300)

myTurtle.ht()

myTurtle.penup()

myTurtle.pendown()

myTurtle.shape("turtle")

myTurtle.color("green")

myTurtle.write("Hello World")

The complete Turtle Graphics documentation can be found here. T

Lesson 13¶

Draw a square with Turtle graphics. Use a for loop to do this. Then write a function called drawSquare that when called uses the turtle to draw a square at a particular location and with a particular size on the screen.

Have More Time?¶

Write a function called isPalindrome that returns true if a string is a palindrome. A palindrome is a string that spelled backwards is the same as forwards. For instance, “radar” is a palindrome. So is “madam i’m adam” and “a man, a plan, a canal: Panama” but you don’t have to handle these as they have spaces and puncutation to deal with. You only have to return true if it is a true palindrome with all punctuation and spelling included.

Write a main program that asks the user for input and then print “This is a palindrome.” or “This is not a palindrome.”

Write a function called intersection that returns the elements of two lists that are common to each other. Then write a test program that asks the user to enter two lists of strings and then prints the items that were common to each other. You can get input from the user with the input function and you can split a string into a list of strings with the split method on a string. So if s is the string ‘Hello World’ then s.split() returns the list [‘Hello’, ‘World’].

Event-Driven Programming and Minesweeper¶

In this part of the class we will create a Minesweeper application. Along the way you’ll learn some things about event-driven and GUI programming. The word GUI stands for Graphical User Interface and refers to programs that run in a window. Minesweeper is one of those applications since it responds to mouse clicks.

A GUI program responds to events that occur while the program is running. The main program for a GUI application is usually not written by the programmer. Instead the main program is provided and is called an event-dispatch loop. Here is some pseudo-code for an event-driven main program.

def main():

while True:

event = mainQueue.getEvent()

dispatch(event)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

In this code the mainQueue.getEvent() blocks if no event is available. A blocking method is a method that waits, without using any CPU time, for an event to become available. When an event is available then the getEvent method returns and the dispatch function looks for a handler to handle the event.

So, as programmers of event-driven programs, we register event handlers with the dispatch function so our event handler gets called when the event occurs that we want to handle. We’ll see this in the next section when we learn a bit about turtle graphics.

To start the Minesweeper application you can copy this code and these pictures to a folder on you computer. The code and the pictures must all be in the same folder on your computer.

You might take a couple of minutes to look over the Python code. The Tile class inherits from the Turtle class. This means a Tile is a Turtle with some extra things attached.

The MineSweepApplication inherits from the Frame class. A MineSweepApplication is a Frame with some extra things attached. A Frame is a widget that is a container. It holds other widgets like Turtles or Tiles for instance.

Lesson 14¶

If you run the starter code you might notice a very small window appear on the screen. Our goal is to fill in that window with a canvas area where we can create turtles (i.e. Tiles), create a menu and get ready to write the code for starting a game.

The code we write in this lesson goes in the buildWindow method of the MineSweepApplication. This is where we are going to write our event handlers and register them so we can process events in our program.

Our goal in these lessons is going to be to understand what the code we are working through does. To begin, let’s give our application a name and create an area where we can draw with turtles. To do this we add this code to the buildWindow method of the MineSweepApplication class.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | self.canvas = tkinter.Canvas(self,width=600,height=600)

self.canvas.pack(side=tkinter.LEFT)

self.master.title("Minesweeper")

theTurtle = turtle.RawTurtle(self.canvas)

theTurtle.ht()

screen = theTurtle.getscreen()

self.screen = screen

|

This code tells the master window (i.e. the root window) to change its title to Minesweeper and creates a canvas where turtles can draw. The tkinter module is a framework for writing our own GUI programs and is cross-platform. You can read all about the tkinter framework here.

To create a menu for our application we create a Menu widget called bar, add a File menu widget to the menu bar and then add a couple of menu commands to the file menu as follows. If you look at your existing code before pasting this in, you will see the tickTock and the newGame functions. Put your code in around this existing code.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 | bar = tkinter.Menu(self.master)

fileMenu = tkinter.Menu(bar,tearoff=0)

def tickTock():

currentTime = datetime.datetime.now()

elapsed = currentTime - self.startTime

elapsedSeconds = elapsed.seconds

self.elapsedTime.set(str(elapsedSeconds))

if self.running:

self.master.after(1000,tickTock)

def newGame():

print("New Game Selected")

fileMenu.add_command(label="New Game",command=newGame)

fileMenu.add_command(label="Exit",command=self.master.quit)

bar.add_cascade(label="File",menu=fileMenu)

self.master.config(menu=bar)

|

Now you can tell the turtle called theTurtle to do some of the commands that you learned above to see that it will draw on the canvas that you have created.

Finally, we create sidebar area to keep track of the number of bombs that are left. Our game will have 40 bombs in a 16x16 grid of tiles. We’ll also keep track of elapsed time.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 | sideBar = tkinter.Frame(self,padx=5,pady=5)

sideBar.pack(side=tkinter.RIGHT, fill=tkinter.BOTH)

timeLabel = tkinter.Label(sideBar,text="Elapsed Seconds")

timeLabel.pack()

self.elapsedTime = tkinter.StringVar()

self.elapsedTime.set("0")

self.timeElapsed = tkinter.Label(sideBar,textvariable=self.elapsedTime)

self.timeElapsed.pack()

bombCountLabel = tkinter.Label(sideBar,text="Bomb Count")

bombCountLabel.pack()

bombEntry = tkinter.Entry(sideBar,textvariable=self.bombVar)

bombEntry.pack()

bombLabel = tkinter.Label(sideBar,text="Bombs Remaining = " + self.bombVar.get())

bombLabel.pack()

self.tileLabel = tkinter.Label(sideBar,text="Tiles Remaining = 256")

self.tileLabel.pack()

|

To keep track of a 16x16 grid in the program we construct a list of lists. Each list is a row of tiles in the minesweeper program. There are 16 of these rows. All 16 rows are put in another list called the matrix. The matrix is a variable in the MineSweepApplication.

The screen is an object that we can use to change the coordinates of the canvas. We can also register shapes with it. When we register a shape we say that we want a turtle to take that shape somewhere in our program.

We get the screen from the initial turtle we created. Then we can set the coordinates to be a 600x600 pixel canvas with (0,0) in the upper left corner. We can then clear the screen and set tracer to 0. The tracer command on the screen tells the screen not to update unless we tell it to update. This speeds up the program so that turtles appear to move very fast when we give them commands. Here is the code that does this. You can add this to the newGame function.

1 2 3 | screen.setworldcoordinates(0,600,600,0)

screen.clear()

screen.tracer(0)

|

We now want to register some shapes. You add this code in buildWindow but NOT in the newGame function. You don’t need to execute this code each time a new game is started. It only has to execute once when the application is started. The code below is necessary because we will have turtles use these shapes later in our program. Some turtles will look like bombs, others flags, and still others will look like tiles. Turtle graphics requires you to register these shapes before a turtle can change its shape.

1 2 3 4 5 | screen.register_shape("bomb36.gif")

screen.register_shape("tile36.gif")

screen.register_shape("flag36.gif")

newGame()

|

Finally, when the program starts the newGame function is called. This function starts the game by creating the mines and tiles and then displaying them in a 16x16 grid.

We still need to complete the newGame function. You write the following code in the newGame function definition. When new game is called there may be an old game that needs to be cleaned up. Since each tile is a Turtle, we can clean up the old game by moving the turtles off the screen. To do this we write a couple of for loops to go through all the rows of the matrix and for each row all the columns of the row. Here is what the code looks like:

1 2 3 | for row in self.matrix:

for tile in row:

tile.goto(-1000,-1000)

|

No game is interesting unless there is some randomness to the game. In Minesweeper we want the 40 bombs to appear at random locations within the game. We’ll create 40 random numbers to go along with the 40 random bombs that we’ll create. The random.randrange(256) function will generate a random number between 0 and 255. Because it might generate a same random number twice (or more) there is a little bit of code to make sure that random numbers in this range don’t repeat (so we get 40 random numbers). This number of bombs is configurable by the user. So we get the number of bombs from the entry box that is configured in the user interface. WHEN YOU PASTE THIS CODE IN THE INDENTATION WILL NOT BE CORRECT. You can highlight the code and press shift-tab to back it up so it lines up with the for row in self.matrix line of code.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 | randomNumbers = set()

numBombs = int(self.bombVar.get())

bombLabel.configure(text="Bombs Remaining = " + self.bombVar.get())

for i in range(numBombs):

r = random.randrange(256)

while r in randomNumbers:

r = random.randrange(256)

randomNumbers.add(r)

|

Next, we create 256 tiles by creating the 16x16 matrix. As we create tiles we’ll count from 0 to 255. If we come to a number that is in our list of random numbers, we’ll make a tile a bomb. Otherwise, a tile is just a tile. Here is code to do this. Again, be careful to line this code up with the for loop in the previous code.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 | self.matrix = []

self.tileNum = 256

count = 0

for rowIndex in range(16):

row = []

for colIndex in range(16):

bomb = (count in randomNumbers)

aTile = Tile(self.canvas,screen,rowIndex,colIndex,self.matrix,bomb,self)

count = count + 1

row.append(aTile)

self.matrix.append(row)

self.screen.update()

self.startTime = datetime.datetime.now()

self.master.after(1000,tickTock)

|

The newGame function concludes with starting a timer to count the seconds since the game started.

Lesson 15¶

Up to this point, the application doesn’t really do anything. The canvas appears, but no tiles or bombs. We need to complete the Tile class to get the program working. Right now the __init__ method in the Tile class has one line in it: the call to super().__init__(canvas). We should keep in mind that the Tile class inherits from the RawTurtle class (which is really just a Turtle itself). There is a lot of information passed to a Tile object when it is created. The canvas it will be diplayed on is passed. The screen object is useful and is passed in as well. The rowIndex is the row in the matrix (starting at 0) that the tile is in. The colIndex again goes from 0 to 15. The matrix is the entire matrix of Tiles. The bomb variable is True if this tile is a bomb and False otherwise. The gameApp variable points back at the game application object for use later. We store all this information in the object. The self variable points at the current object so if we write self.somevariable we are referring to somevariable in the object pointed to by self which is the current object. So to store gameApp in a Tile object, we write

self.gameApp = gameApp

and we add this code to the __init__ method in the Tile class. Write similar code to store all the other variables in a tile object.

Remember that self is a turtle in the Tile class because a Tile is a Turtle since the Tile class inherits from Turtle. We want to tell the tile to pick up its pen and to take on the shape of a tile. To change the turtle’s shape we write this:

self.shape("tile36.gif")

Now we also want the tile to go to the correct location on the screen for its row and column. Since the upper left corner is (0,0) and the width and height are 600 pixels, where should a Tile with rowIndex and colIndex be located? Figure this out and then tell self to go there using a goto command. Add that code to the __init__ method of the Tile class.

In a GUI application we write event handlers. An event handler gets called when an event like a button press or mouse click happens in a program. We tell our program which event handler to call by registering the event handler. When we click the left mouse button, we want to run some code in our program. Here is how we register an event handler in our application. THIS CODE IS ALREADY PROVIDED, but is included here so you see how the event handler is registered. You don’t have to write anything more for this to be defined and registered.

1 2 3 4 | def leftClickHandler(x,y):

self.whenLeftClicked()

self.onclick(leftClickHandler)

|

That’s it for lesson 15!

Lesson 16¶

Now it gets a bit more complicated. We’ll start with the right-click handler called whenRightClicked. When we right-click on a tile we will change its shape to a flag. Look in the __init__ method of the Tile class to see how the shape of the turtle was changed to a tile. Then, change the shape to a flag36.gif. Don’t forget to update the screen after you have done this.

When the left button is clicked we want to either end the game and display all the bombs, or clear all the adjacent tiles that are not next to bombs and possibly display a number. We’ll start by checking to see if the turtle/tile is visible or not. This code gets added into the whenLeftClicked method.

If the tile is visible, then we want to know whether it is a bomb or not. If it is a bomb we’ll change it’s shape to bomb and then display all the other bombs and end the game. Here is some code to get us started. Again, this goes in the whenLeftClicked method.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 | if self.isvisible():

if self.bomb:

self.shape("bomb36.gif")

self.screen.update()

tkinter.messagebox.showinfo(\

message="You blew up!! Game Over!!", \

title="Game Over!!!")

self.gameApp.gameOver()

|

Notice that this code calls gameOver on the MineSweepApplication class. The gameOver method of the MineSweepApplication class should go through each row in the matrix and for each tile in each row it should call the gameOver method on each Tile object. After doing this, don’t forget to update the screen with this statement:

self.screen.update()

The tile’s gameOver method should display itself as a bomb (if it is a bomb). You may also want to disable all mouse clicks. You can do this in the Tile gameOver method by writing this:

self.onclick(None)

self.onclick(None,btn=2)

So, to recap, in this lesson you should have added code to both the gameOver methods of Tile and the MineSweepApplication classes and you should have added code to both the whenRightClicked and the whenLeftClicked methods of the Tile class. That’s enough for lesson 16.

Lesson 17¶

Now we finish the application by clearing non-bomb tiles from the screen and their non-bomb neighbors. To do this we add an else statement to the whenLeftClicked method as outlined below.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | if self.isvisible():

if self.bomb:

# stuff we wrote in lesson 16

else:

# stuff we write in lesson 17

self.screen.update()

|

To complete this code we want to do the following. First we want to hide the tile and decrement the number of tiles in the game. We can do this by writing a line of code like this:

self.ht()

self.gameApp.decTileNum()

But, for this to work we’ll need to define a decTileNum method on our MinesweepApplication class as follows.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 | def decTileNum(self):

self.tileNum = self.tileNum - 1

self.tileLabel.config(text="Tiles = " + str(self.tileNum))

numBombs = int(self.bombVar.get())

if self.tileNum == numBombs:

self.gameOver()

tkinter.messagebox.showinfo(\

message="You didn't blow up! Congratulations!!",\

title="You Won!!!!")

|

The next bit of code goes in the whenLeftClicked method in the new else part that we are defining. We need to make all the neighbor tiles of this tile disappear if they are not bombs. To do this we want to make a list of the neighbors that are not bombs and count them as well. This is a little complicated but picture counting all the neighbors of a tile and adding them to a list. Here is code that does this.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 | neighbors = []

bombNeighbors = 0

for i in range(self.rowIndex-1,self.rowIndex+2,1):

for j in range(self.colIndex-1,self.colIndex+2,1):

if i >= 0 and i < len(self.matrix) \

and j >= 0 and j < len(self.matrix):

if i != self.rowIndex or j != self.colIndex:

neighbor = self.matrix[i][j]

if not neighbor.bomb:

neighbors.append(neighbor)

else:

bombNeighbors = bombNeighbors+1

if bombNeighbors == 0:

for neighbor in neighbors:

neighbor.whenLeftClicked()

|

Then, once we have the list of neighbors, if none of the neighbors are bombs, we can uncover the neighbors by going through the list of neighbors and calling whenLeftClicked on them.

The last little bit is to display a number in place of a tile to indicate the number of bombs that are adjacent to the tile. This code will do that. AGAIN, make sure that this code get’s indented correctly. It should line up with the if bombNeighbors == 0 if statement above it.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 | if bombNeighbors > 0:

if bombNeighbors == 1:

color = "blue"

elif bombNeighbors == 2:

color = "green"

elif bombNeighbors == 3:

color = "red"

elif bombNeighbors == 4:

color = "purple"

else:

color = "black"

self.color(color)

self.left(90)

self.forward(10)

self.write(str(bombNeighbors),align="center",\

font=("Arial",18,"bold"))

self.right(90)

self.forward(10)

|

Don’t erase the screen.update() at the end of the method. That’s important that it is the last thing done in your whenLeftClicked method. That’s it! You now have a complete Minesweeper application! Congratulations on learning some GUI programming in Python.

Lesson 18¶

There is no code to write for this lesson, just an explanation of some code you copied.

You might have noticed that the number of bombs configurable. To do this requires input from the user. A nice way to do this is with an entry box and what is called a StringVar in Tkinter. Here is how to code an entry box in Tkinter. You can find this in the application if you look for it.

# This is a label widget. Packing it puts it at the top of the sidebar.

bombCountLabel = tkinter.Label(sideBar,text="Bomb Count")

bombCountLabel.pack()

# This entry widget allows the user to pick a width for their Minesweeper.

# With the self.bombVar variable below you can write self.bombVar.get() to get

# the contents of the entry widget and self.bombVar.set(val) to set the value

# of the entry widget to val. The type of the value is a string so if you want

# an integer you must write int(self.bombVar.get())

bombEntry = tkinter.Entry(sideBar,textvariable=self.bombVar)

bombEntry.pack()

You can read the comments above to see how the StringVar can be used to set the number of bombs of the Minesweeper application. Then you can use the value by calling get as the comment above says. For instance, to get the number of bombs of the minesweeper application, we could write this.

bombCount = int(self.bombVar.get())

The other nice feature of this application keeps track of elapsed time in seconds. This is done by using the after method on the Tkinter root window and using the datetime module. By writing this code in your MineSweepApplication class.

self.master.update(1000,ticktock)

The ticktock method is called after approximately one second. When new game is selected, the startTime is recorded by using the datetime module’s now function as follows.

import datetime

startTime = datetime.datetime.now()

Then the code does the same to get the currentTime in the ticktock function.

currentTime = datetime.datetime.now()

elapsedTime = currentTime - startTime

# now elapsedTime.seconds is the number of seconds the game has been playing

Once you have the current time, a label is updated to display the current number of elapsed seconds in your game.

You might also display a final score for your application which might be some measure of how many bombs you uncovered with the time factored into it as well. Here is the final solution to these exercises.

Have More Time?¶

If you have more time you could do one of two things. You can improve the Minesweeper application. For instance here are some enhancements that might be added.

- You could allow the flag to be turned on and off on a tile. Right now when you right-click a tile it turns the flag on, but you can’t turn it off again. You could add code to allow this to be turned on and off.